Dimensions of neck and low back pain

The scientific approach to neck and low back pain (NLBP) started with investigations in the 1930s of the occupational environment and the changes in spinal structures due to loads and postures. Since then and up to the 1980s, the leading principle of NLBP prevention was postural adjustments, and rest was advocated as the mainstay of treatment. In 1987 the Quebec Task Force (QTF) on Spinal Disorders published a comprehensive literature review on back pain accounting for 450 relevant studies, which was followed by a specific review on cervical “whiplash”. This encouraged numerous studies and guidelines from professional organisations in the 1990s, with an important shift from rest towards activity and exercise as the core of NLBP management.

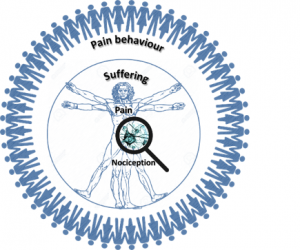

Today NLBP is understood as a health problem where biological, psychological, behavioural, and social factors are intertwined. Within this theoretical framework, the biological dimension of pain is mainly related to the understanding of the originating noxious stimuli (nociception), while it has been shown that the actual suffering is mostly driven by psychological factors influenced by the individual personality, attitudes, and resilience in illness. Moreover, the disability experienced is influenced by several high-level factors, such as socioeconomic status, levels of insurance, levels of health literacy, and workplace physical and psychological stressors.

Thus, NLBP can be seen as a health problem that operates across a number of different dimensions: a small biological dimension, where mechanical and biochemical processes lead to nociceptive stimuli; a large biological dimension at the level of joints, muscles and other body structures involving the physical sensation of pain as well as the movements and activities that influence it; a psychological dimension at the level of the individual that suffers of pain; and the large social dimension in which the pain behaviour is manifested. Moreover, NLBP is a dynamic process where the different aspects that can be assessed change over time following complex patterns. Whilst the biological causes of pain, its perception or the impact on the patient’s life can improve, other factors can at the same time be barriers to improvement.

Biological factors

It is common to distinguish between nociceptive pain, neurogenic pain and psychogenic pain. The individual patient may show signs or symptoms of any or all types of pain. Nociceptive pain is caused by activation of pain receptors (nociceptors) that are present in most tissues such as skin, muscle, fasciae, joints, and blood vessels. They are free nerve endings that inform the central nervous system of a noxious stimulus that can threat tissues (subjectively painful). Neurogenic pain originates in the peripheral and central nervous system. Both mechanisms can be intermingled. On the other hand psychogenic pain is unusual, appearing in psychotic states such as deep depression or schizophrenia.

Nociceptors typically have a high stimulation threshold, but that threshold can be affected, such that even weak mechanical stimulation that is innocuous, such as normal joint movements can elicit pain. Such sensitisation can be increased by the presence of particular substances, creating cascade effects. This can lead to chronic pain states. Chronic states are characterised by a concentration in cerebrospinal fluid of substances like nerve growth factor (NGF), which is produced and released by peripheral tissues following noxious stimuli.

The onset of NLBP can be caused by obvious causes like disease or injury in spine structures and joints. But more often it is caused by “silent” changes not localised in the spine, which can actuate on spinal pain receptors.

Epigenetic research has begun to illuminate how the expression of candidate genes that contain certain predispositions for illness, and their resulting behavioural phenotypes, are displayed. In addition to these genetic predispositions, variables such as stress can alter their phenotypic behavioural expression, and have lasting effects both behaviourally and psychosocially.

Psychosocial factors

Beliefs and cognitions about pain, such as fear-avoidance beliefs, illness perception and the emotional status of the patient are some of the most important factors that may moderate or exacerbate the sensation of pain given a certain noxious stimulus, and its vulnerability and resilience. These psychological factors are particularly relevant in the transition from acute to chronic NLBP.

Psychological processes are highly intertwined and operate together as a dynamic system, where there is not a “Cartesian”, proportional relation between nociception and pain experience and behaviour. For instance, emotional effects of pain due to past experience or beliefs can lead to catastrophizing and avoidance behaviours, like anticipated pain when patients feel that a wrong movement or activity could result in, or worsen, their pain. This has a major influence on the level of pain-related disability, which varies between individuals and within the same individual in different stages.

The current understanding of how psychological processes can produce painful sensations is based on the theory of the “neuromatrix of pain”, which postulates that such sensations are generated in the central nervous system (the brain and spinal cord), rather than in damaged tissues. In such a model, cognitive and emotional inputs can open or close “gates” of the neurotransmitters of pain. This theoretical model is widely used by researchers to explain how pain is developed and expressed, and that knowledge has been valuable to define reasoned guidelines and heuristics to manage pain in general, and NLBP in particular.

Socioeconomic factors

Socio-economic factors include the relation and status of the patients with respect to family and other people, gender, cultural attitudes and beliefs, social activities, etc. These factors have a direct, bidirectional relation with psychological factors. Focusing on a working population, the social dimension of NLBP is mainly related to its impact on professional life, which can also involve an economic perspective of the problem.

Pain-related psychological processes are affected by the type of job — in part by the physical demands that may influence on NLBP, but also due to other types of stressors and by the social role of the worker. Pain coping attitudes and behaviours are very dependent on the employment status, salary level, relation between worker and employer, risk of job loss, and the conditions of insurance protection.

At the same time, NLBP can have an important impact on the socioeconomic context of the workers. The sick role often implies a certain degree of functional loss, or pain-related disability, with resulting underperformance and absence from work. This has a clear negative economic impact for autonomous workers or employers, but sometimes also for employees in terms of lower income, depending on insurance conditions, although in relation to work-related injuries or road accidents (the typical case of cervical whiplash) there can be monetary compensations as well.

The situation is further complicated in NLBP with respect to other types of sickness, due to the non-specific nature of pain in the majority of cases, and the fact that it often improves naturally over the course of a few weeks. This creates a great degree of uncertainty on the cost-effectiveness of intervention measures to reduce sick periods and restore the physical function, although it can be modelled given the sufficient amount of statistical information.

References

- Carlsson CA, Nachemson A. (2000). Neurophysiology of back pain: current knowledge. Neck and Back Pain: the scientific evidence of causes, diagnosis, and treatment. Lippincot Williams & Wilkins, 149-63.

- Gatchel, R. J., Peng, Y. B., Peters, M. L., Fuchs, P. N., & Turk, D. C. (2007). The biopsychosocial approach to chronic pain: Scientific advances and future directions. Psychological Bulletin, 133(4), 581-624. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.133.4.581

- Smith, R. C., Fortin, A. H., Dwamena, F., & Frankel, R. M. (2013). An evidence-based patient-centered method makes the biopsychosocial model scientific. Patient Education and Counseling, 91(3), 265-270. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2012.12.010

-

Melzack, R. (2005). Evolution of the Neuromatrix Theory of Pain. The Prithvi Raj Lecture: Presented at the Third World Congress of World Institute of Pain, Barcelona 2004. Pain Practice, 5(2), 85-94. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1533-2500.2005.05203.x